The World Health Organization explains that "Malaria is caused by a parasite called Plasmodium, which is transmitted via the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes. In the human body, the parasites multiply in the liver, and then infect red blood cells. Symptoms of malaria include fever, headache, and vomiting, and usually appear between 10 and 15 days after the mosquito bite. If not treated, malaria can quickly become life-threatening by disrupting the blood supply to vital organs." Malaria is particularly lethal small children and pregnant women, and while there isn't a vaccine there are extremely effective treatments available, and people can avoid mosquito bites by using insect repellent and sleeping under Long-Lasting Insecticide-treated Nets (LLINs).

Malaria is an enormous problem in Senegal, and, unfortunately, the region of Kédougou has some of the highest malaria rates around. Thanks to Universal Coverage programs and increased access to Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs), many more people are sleeping under LLINs (at least during rainy season) to avoid malaria and getting effective treatment if they are infected. There are PCVs doing amazing malaria eradication work across Senegal, and you can click here to read the fantastic post that my friend Annē wrote about an ongoing anti-malaria project in the Kédougou region.

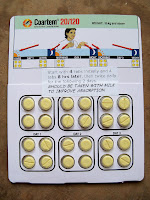

Like many, many people I know, my little host sister Diamé came down with malaria last year. Thankfully, my host family lives within walking distance of a health structure, understands the importance of early treatment, and has the means to pay the small consultation fee to see the nurse to get malaria medication, which is free. It's never fun to see a sick kid, but as far as children-with-malaria-scenarios go, Diamé's played out pretty ideally - in the evening Diamé's mom saw she was listless and feverish, the next morning she took her in for an RDT, came home with a pack of Coartem (the locally available brand of malaria medication) and before long Diamé was back to normal. All too often, people put off seeking treatment, and by the time they get to a health structure they're so sick that they need more intravenous medication and fluids, which are expensive and can require hospitalization.

|

| Diamé and I in 2012 |

Early treatment is great, but prevention is even better, and I'm really hopeful that this year Diamé won't get malaria at all. In addition to upcoming Universal Coverage follow-up bed-net distributions, there are plans to a implement seasonal malaria chemoprevention (preemptive treatment) program for all children under the age of 10 living in high transmission zones. It's an ambitious approach, but it has the potential to have a truly enormous impact on malaria in Kédougou.

|

| I don't want these kids to get malaria. |

I'm excited about seasonal malaria chemoprevention because it's a way to help break the cycle of malaria transmission Anopheles mosquitoes become infected with Plasmodium when they bite a person who is carrying the malaria parasite; the mosquito becomes infected and then passes the parasite on to the next person it bites. If kids are on chemoprevention it means that they'll be protected from malaria, and they'll also avoid being carriers, which will help to reduce transmission rates and protect the entire community. Additionally, as someone who's been on preventative malaria medication of one kind or another for the last two years, it's really good to know that my little host brothers and sisters will be given a chance to benefit from the same kind of protection that I had during my service. They deserve at least that much.

If you'd like to know more about malaria and the work that's being done to eradicate it, please take a look at Stomp Out Malaria, or check out what the CDC or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have to say about the fight against malaria.